The podcast of the University of Colorado Consortium for Climate Change and Health

Episode 10: Climate Change and Water Security

For the season finale, Cam and Jake chat with Dr. Kathy James, and learn how climate change threatens water quality and quantity around the globe.

Biography:

Dr. Kathy James earned her masters in engineering from CU Boulder, her masters in public health and PhD from the Colorado School of Public Health. She is an epidemiologist with considerable expertise in environmental systems. In the past, Dr. James has studied the long-term health effects of cadmium, arsenic, and other metals that can contaminate water supplies, and has extensive experience studying disease and environmental exposures in the San Luis Valley of Colorado. Currently, she is an assistant professor in the department of environmental and occupational health and the department of epidemiology at the Colorado School of Public Health, a member of the University of Colorado Consortium for Climate Change and Health, and our go-to expert for information on the effects of climate change on water quality and quantity.

Episode Highlights:

Before we dive in, check out the definitions for a few terms we use in this episode:

Drought

According to Dr. James, drought is a “change in precipitation patterns that reduces the amount of accessible water currently needed in that location”. NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center breaks down the term “drought” into four different entities: hydrologic drought (occurs when low water supplies become manifest), meteorologic drought (prolonged period of low precipitation or water input), agricultural drought (occurs when agricultural production suffers due to reduced water supply), and socioeconomic drought (reflected by water shortage-induced changes in social and economic factors, which are discussed later in the episode).

Below, a picture from WETA of dust transported from the Midwest to Washington, D.C., due to the historic droughts that ensued during the Dust Bowl.

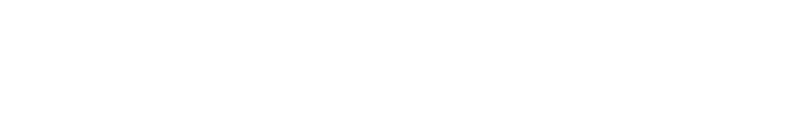

Aquifer

In simple terms, an aquifer is an underground store of water, as illustrated above in the picture from National Geographic.

Water Insecurity

According to UN Water (the United Nations’ workgroup on water and sanitation), water security is the “capacity of a population to safeguard sustainable access to adequate quantities of acceptable quality water for sustaining livelihoods, human well-being, and socio-economic development, for ensuring protection against water-borne pollution and water-related disasters, and for preserving ecosystems in a climate of peace and political stability.” Check out UN Water’s “water security” infographic here.

Water Insecurity, then, is the absence of this capacity. Below, a CNN picture from of the critical water shortage in Cape Town, South Africa, during the summer of 2018.

Heavy Metal

“Heavy metals”, in the context of water quality, refer to a group of metals and metalloids that can have widespread toxic effects in humans. They are (approximately) circled in the periodic table below on the left.

While not discussed in this episode, “heavy metal” also refers to the high-decibel music genre channeled by bands like Iron Maiden, pictured below on the right in an image from The UK Times.

Climate Refugee

In this podcast and in the media, the term “climate refugee” refers to an individual who has been displaced by climate change. This may be an acute environmental disaster like a hurricane, or a more insidious change, like a catastrophic drought. Below, an image (Jonas Gratzer/Getty Images) of Kiribatians displaced by flooding, which is a growing problem for small island nations as sea levels rise due to global climate change.

Of note, there is some disagreement about the use of this phrase, as the term is not recognized in international law, and the term “refugee” typically refers to somebody who has crossed an international border. You can read more about the nuances behind this term at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) website.

Carcinogen

The term “carcinogen” refers to a substance that can cause cancer. In this episode, we use the word in our discussion of toxic heavy metals. Other commonly-mentioned carcinogens include asbestos and cigarette smoke. For those interested in learning more, a lengthy list of carcinogenic compounds is enumerated on the American Cancer Society website, linked here.

Inequity

In this episode and others, “inequity” refers to the fact that different populations experience the effects of climate change differently. In other words, climate change will affect all of us; depending on other factors in our lives and communities, we will experience it differently. Dr. James alluded to a Pinterest meme which illustrates this concept, and which we were able to track down and post below.

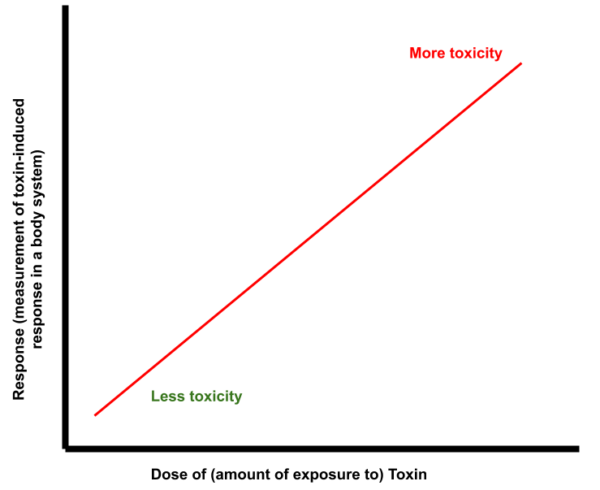

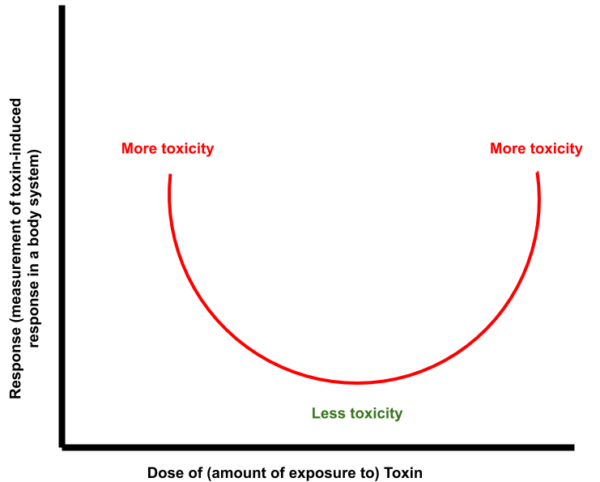

Dose-Response Curve

“Dose-response curve” refers to a plot of the effects of increasing doses (or amounts) of a toxin. On the left is a crude example of a dose-response curve, in which increasing amounts of a toxin result in a linear increase in the degree of toxicity. On the right is a “U-shaped dose-response curve”, which Dr. James references in the interview in the context of manganese. Substances that have a U-shaped dose-response curve are essential at low doses to make our bodies function–without them, we can get sick. However, too much of a substance with a U-shaped dose-response curve can cause toxicity. In addition to manganese, other substances that have U-shaped dose-response curves include iron, zinc, and copper.

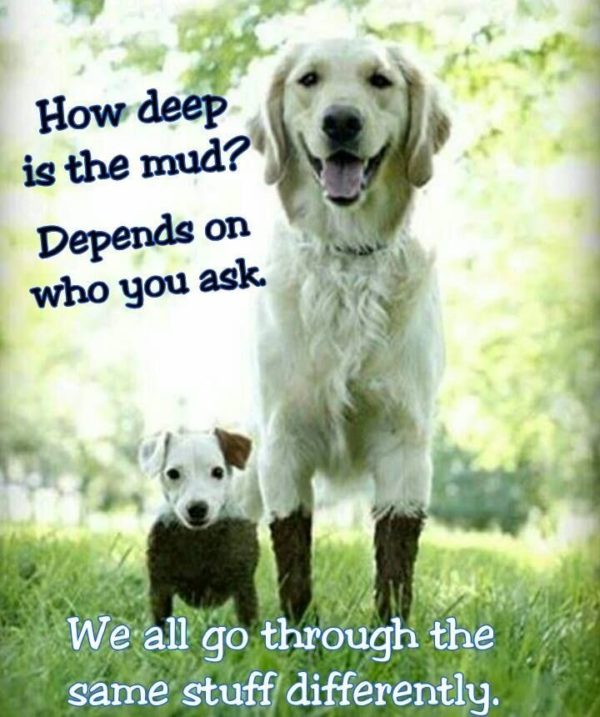

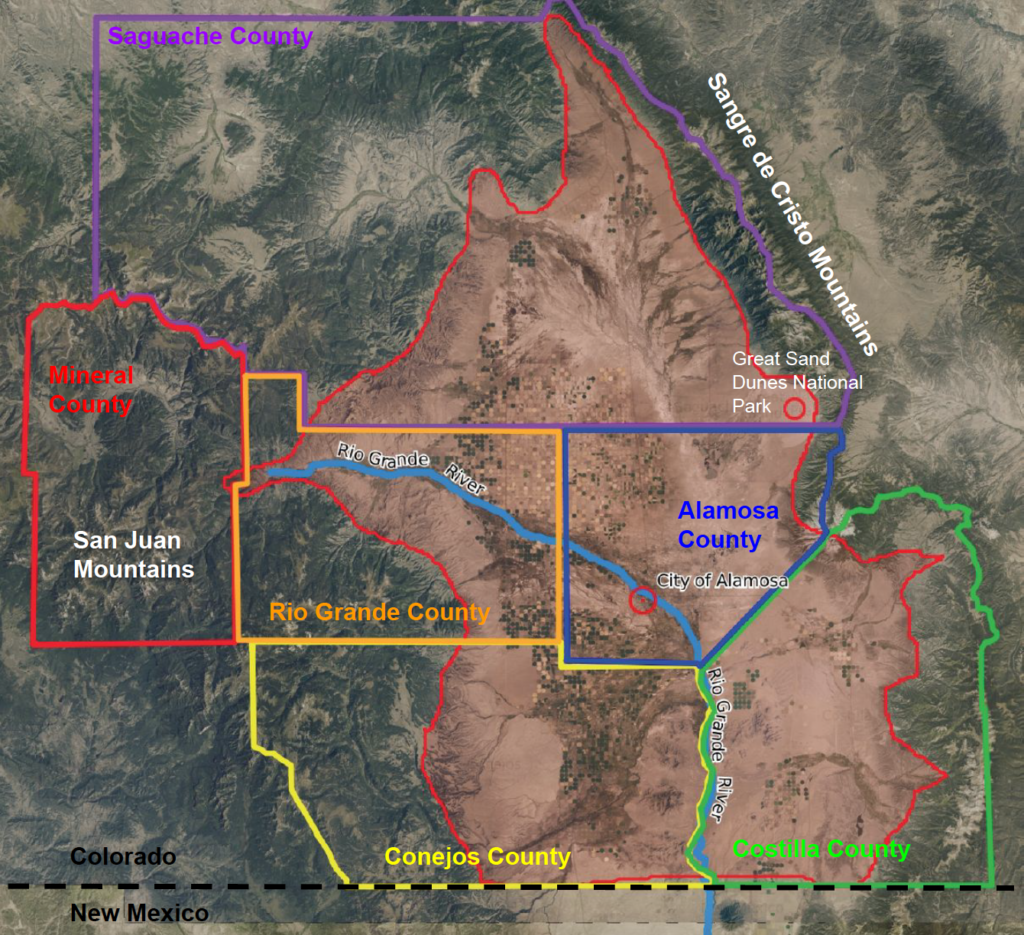

San Luis Valley of Colorado

The San Luis Valley (SLV) is a culturally-rich agricultural region in southern Colorado that forms the headwaters of the Rio Grande River. It is home to the town of Alamosa and the Great Sand Dunes National Park, and has been studied extensively by researchers at the Colorado School of Public Health in part due to its experience of severe drought in recent decades.

Below, a map of the SLV produced using publicly-available software.

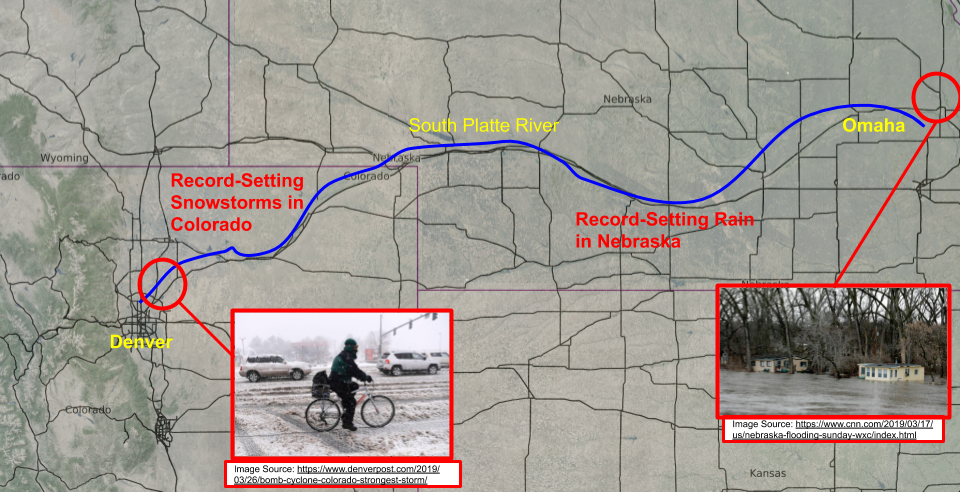

To kick off our exploration of the effects of climate change and water, Dr. James describes how weather extremes can influence water quality and quantity. She recalls the record-setting “bomb cyclone” in Colorado in the early spring of 2019, as well as the historic flooding in farming communities in downriver Nebraska.

Below, a map produced with Caltopo software and overlaid with images from the Denver Post and CNN.

The flooding in Nebraska was driven by two extreme weather events–extreme rain in Nebraska and extreme snow upstream in Colorado–and events such as these are projected to become more frequent with climate change. The consequences were severe: many agricultural communities and cattle herds in the Midwest were decimated by the floods. We explored how floods can compromise water quality in our previous episode with Dr. Carlton, which you can listen to here.

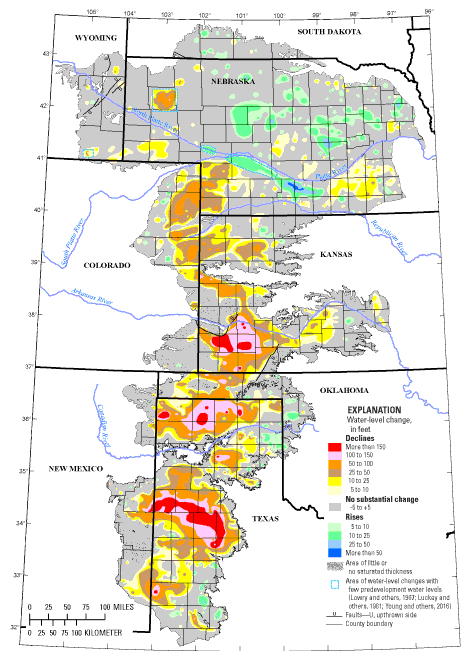

Unfortunately, that’s not the end of the story. Climate change also threatens water quantity and quality by exacerbating drought, which in turn can lead to disequilibrium of aquifer systems. Two aquifers that Dr. James mentions in the episode (and which are particularly relevant to our livelihoods in Colorado) are the Rio Grande Rift and the Great Plains Aquifers, displayed below in two images from the USGS:

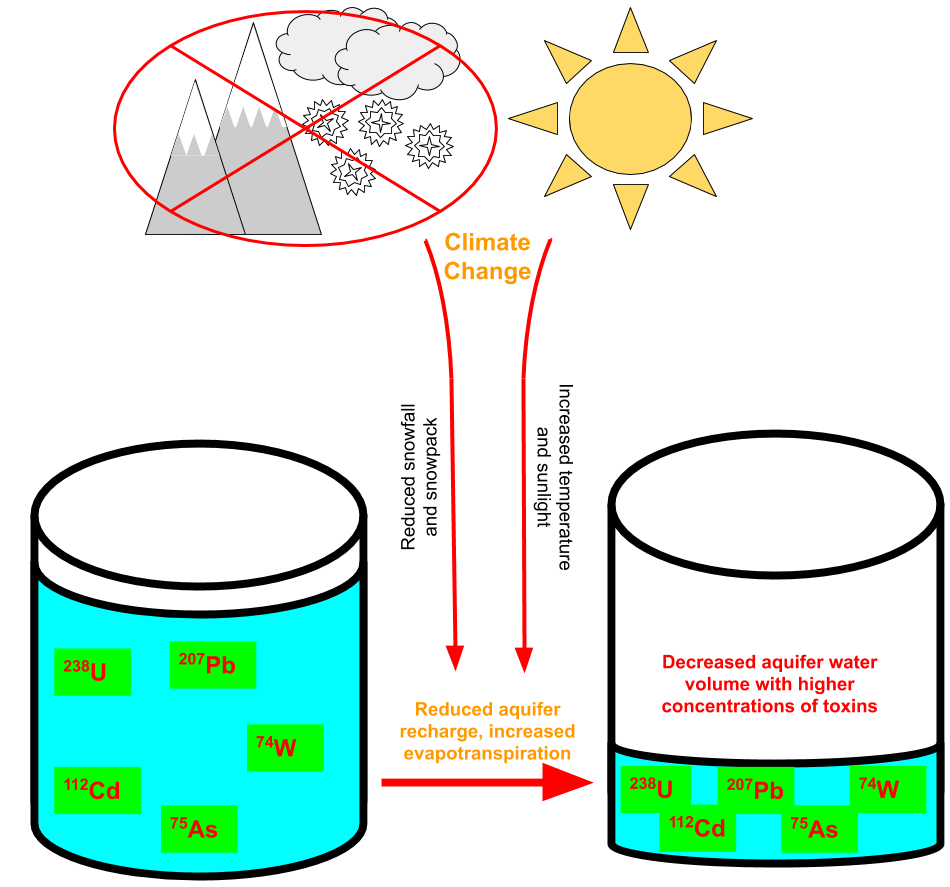

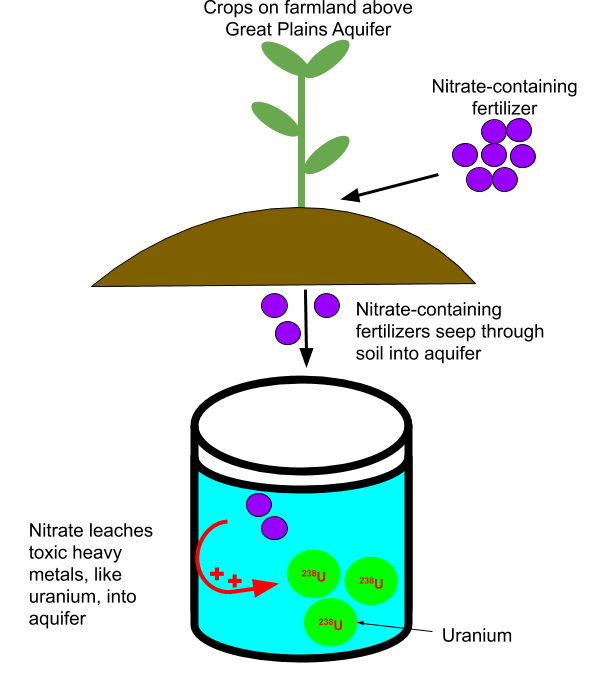

How does climate change threaten aquifers? Specifically, we expect climate change to further reduce the amount of water stored in our aquifers and further increase the amount of toxic heavy metals in the water that remains. Take a look:

Above, an illustration of how increased evapotranspiration (from increased temperature and sunlight) and reduced aquifer recharge (from decreased snowpack) can accelerate reductions in aquifer storage. This, in turn, concentrates heavy metals in the water supply.

While climate change is not responsible for nitrate fertilizers seeping into our aquifers, it is reducing the amount of stored water, which means higher concentrations of nitrate-leached heavy metals like uranium.

Next, we ask Dr. James how these climate-related changes to water quality and quantity can affect human health. In the interview, she groups these effects into three different categories:

Health effects of heavy metal exposure

Water chemistry might seem like a wonky subject, but it is important to consider to understand the serious health implications that can arise from climate-related changes to aquifers. As an example, consider arsenic, which is a heavy metal that has been found to be elevated in the San Luis Valley:

Arsenic is considered a “systemic toxicant”, meaning that it has widespread effects on numerous human systems. As a few examples, arsenic has been implicated in:

- heart disease

- lung disease

- skin disease

- kidney disease

- neurocognitive disease

- and several cancers

You can read more about the health effects of arsenic exposure in this brief review from the WHO. For a deeper, Colorado-specific dive, check out Dr. James’ study of the cardiovascular effects of arsenic exposure in a population in Alamosa.

Of course, arsenic is just one of many heavy metals that can cause systemic illness in people who ingest it. For an abridged review of the health risks of other heavy metals, you can explore this resource here from Kansas State University.

Population health effects of water insecurity

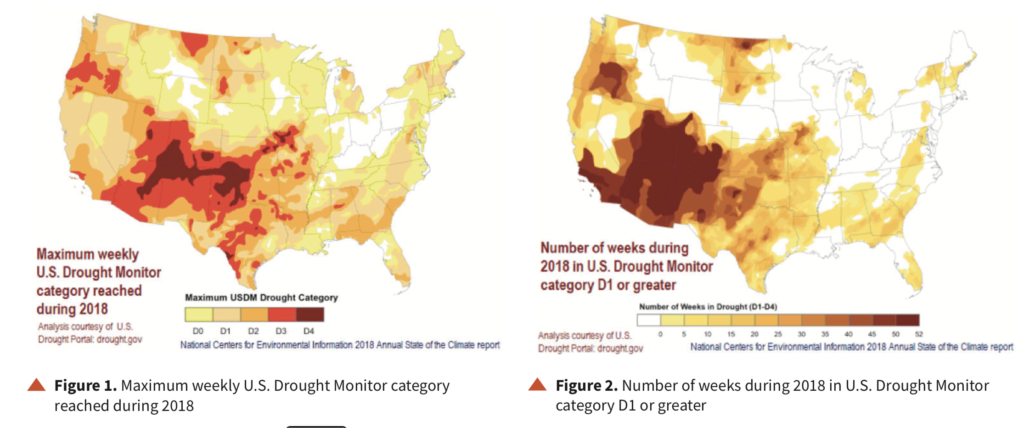

Above, a map from NOAA and the National Integrated Drought Information System detailing the expansive drought in 2018. That year, parts of Colorado were in a state of “exceptional drought” (D4), which is the most severe rating on the drought scale.

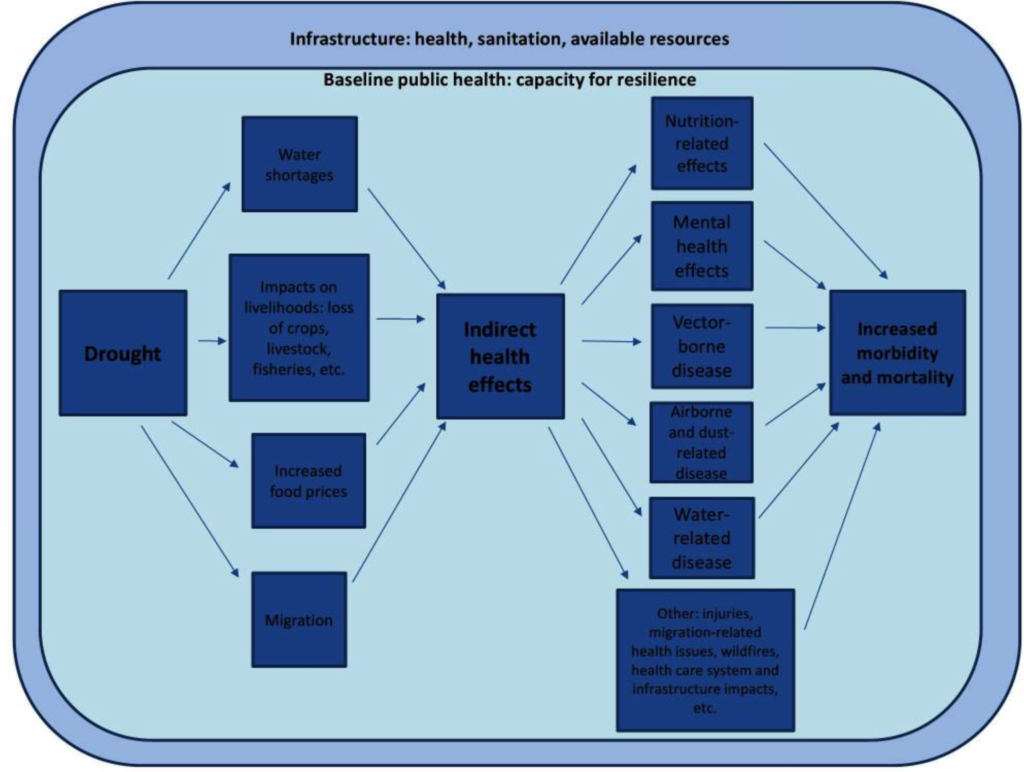

Drought means much more than low precipitation. As Dr. James explains, drought can have sweeping effects on the economy and on the resilience of human communities. For example, drought can reduce agricultural output (thereby compromised the economic livelihood of communities and raising the prices of commodities), spur migration, and have health consequences such as increased rates of mental illness. Many of these effects are illustrated in the figure below, adapted from a review by Stanke et al. (2013):

Water insecurity and violent conflict

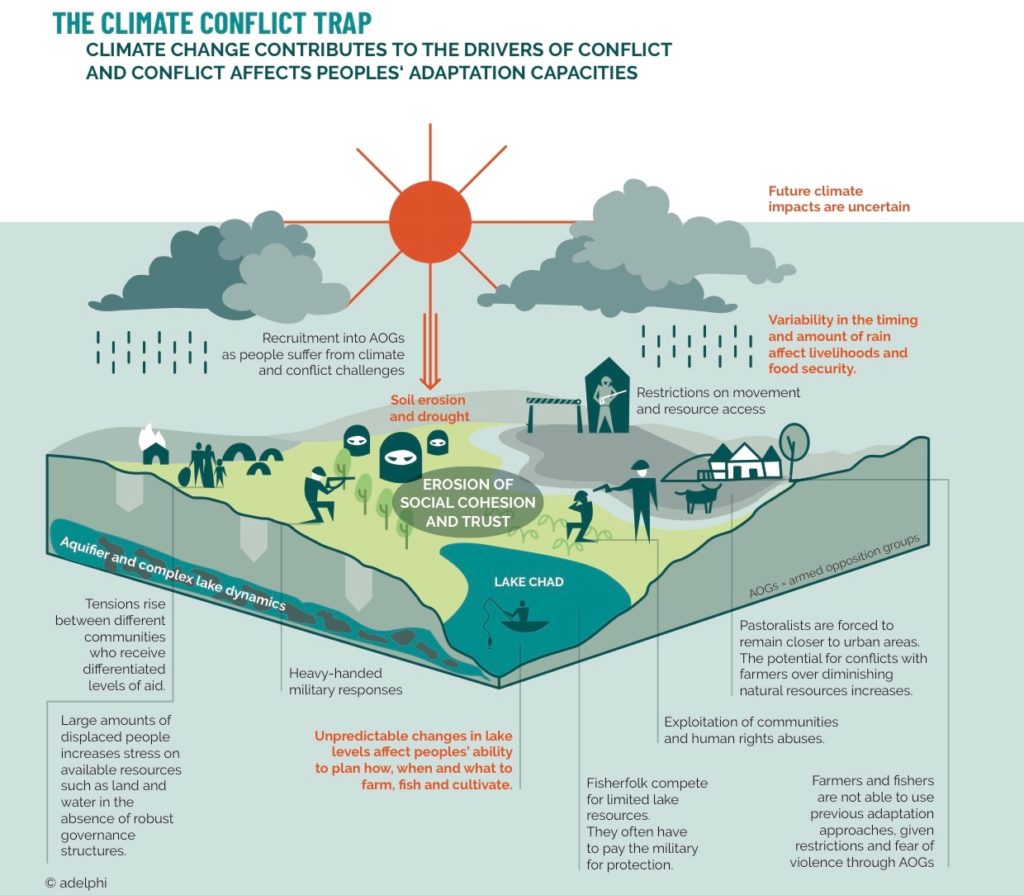

At several points in the episode, Dr. James emphasized her concern that the commodification of water in times of water shortage can alter power dynamics and lead to violence. The links between climate change and conflict are complex, and Dr. James only gave us a cursory overview in the interview. However, drought has been implicated as a factor in the rise of Boko Haram in the Lake Chad region of Africa, and as a factor in the precipitation of the Syrian Civil War (which you can read more about in this paper here). Below, an illustration of how drought interacts with geopolitical violence in the Lake Chad region, adapted from a research figure produced by the Adelphi think tank.

To close out this episode, we ask Dr. James how we can ensure water security here at home. She boils it down to three domains:

Conserve

Consume water-intensive foods in moderation

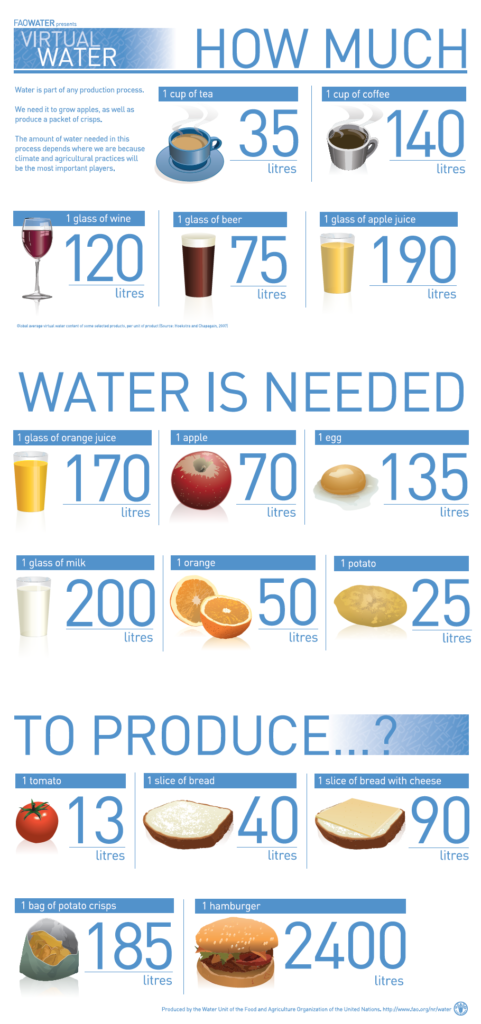

Certain foods require significantly more water to produce than others. Beef is definitely a problem, as are other foods that you might not suspect. For more, check out the infographic from the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations below:

Keep watersheds clean

Colorado is a headwaters state, which means we need to keep our waters clean so that we can fulfill our commitments to our downstream neighbors. As an individual, you can contribute and volunteer your time to groups that organize community efforts to clean our waterways. Below, a Groundwork Denver team engaged in river restoration efforts.

Shownotes

background readings and resources for the interested listener: