The podcast of the University of Colorado Consortium for Climate Change and Health

Episode 4: Climate Change and Air Quality, Part 1

Jake and Cam sit down with Dr. Jim Crooks to discuss how climate change affects ozone and particle pollution in our air, and how this pollution harms our health.

Biography:

Dr. James Crooks is an environmental epidemiologist, statistician, and associate professor at National Jewish Health, a respiratory research hospital in Denver, where he holds the rank of associate professor. Dr. Crooks earned his Ph.D. and M.S. from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2005 and 2006 and completed a 2 year post-doctoral fellowship at Duke University. Afterwards, he fulfilled a seven year stint as a scientist at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development. He then moved to National Jewish Health in 2015, and there has built a research program in air pollution health effects with a focus on climate-sensitive extreme events such as wildfires and dust storms. He has authored 30 peer-reviewed publications, advised the U.S. embassy in Sarajevo on air quality in Bosnia and Hercegovina, and served on two EPA air pollution science review panels. He currently co-directs the Program on Environmental Epigenetics at National Jewish Health and leads the Respiratory Disease and Air Pollution working group of the University of Colorado Consortium for Climate Change and Health, and works as a clinical assistant at the Colorado School of Public Health. Most importantly, he is a husband and father of two middle school aged boys.

Episode Highlights:

To kick off the episode, Dr. Crooks talks ozone.

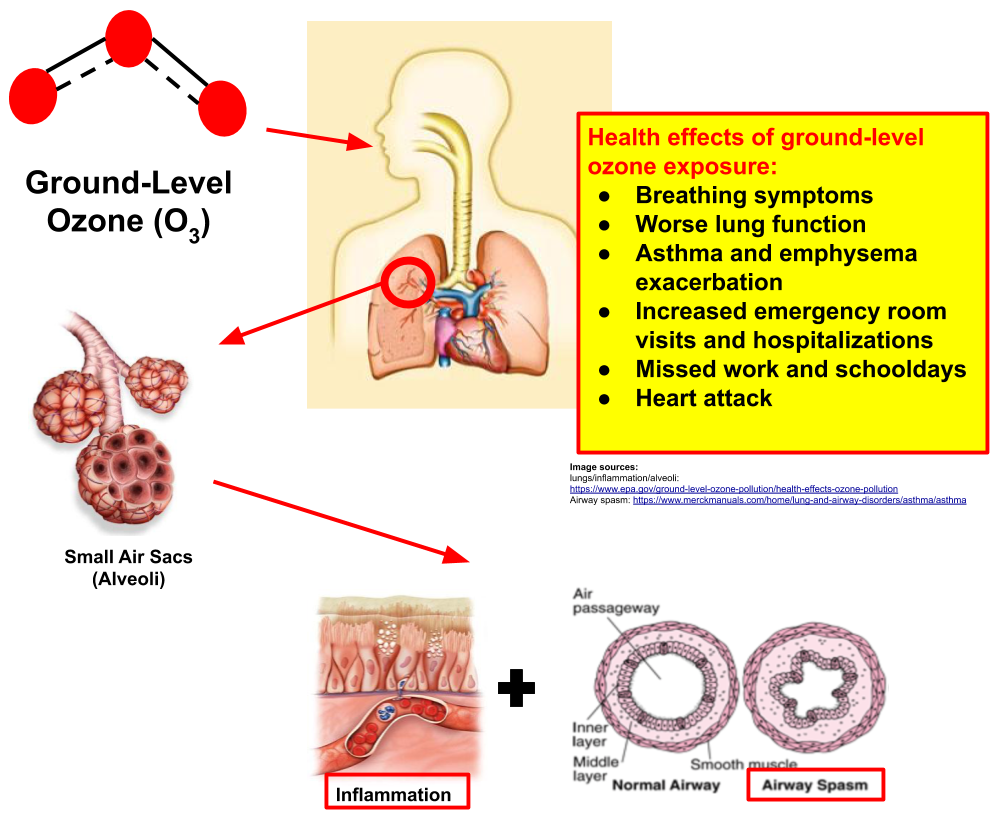

Before we discuss the health effects of ozone, it’s important to remember that we are talking about ground-level (AKA “tropospheric”) ozone. The other ozone (of “ozone hole” fame) exists way higher in the stratosphere. Both are the same molecule, but we are generally referring to ground level ozone when we are talking about air quality.

Stratospheric Ozone

Check out the video above for a brief overview of stratospheric ozone–including what it does, a history of the “ozone hole”, and the success of the Montreal Protocol–created by NASA and the Goddard Space Flight Center. If you want to learn more about the ozone hole, NASA has other cool resources available here.

Tropospheric (“ground level”) Ozone

Tropospheric (“ground level”) Ozone

Above is a picture of an interstate sign on a high ozone day, with which many of us in the Front Range of Colorado are quite familiar. Ozone alerts, like the one in the picture above, refer to high levels of ground level ozone that can be harmful for our health.

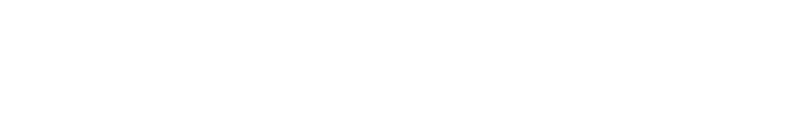

So ozone in the stratosphere acts like sunscreen for the earth, in that it protects us from harmful ultraviolet radiation from the sun. On the other hand, ground level ozone is bad for our health. How is this ground level ozone formed? The EPA summarizes it nicely in the diagram below:

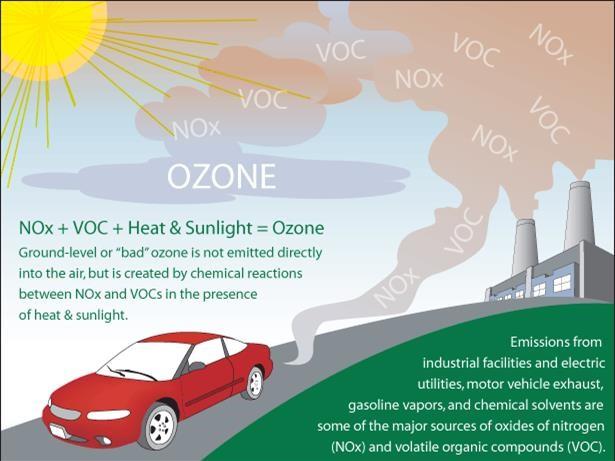

As you can imagine, on hot days with lots of ozone precursors in the air, there can be considerable amounts of ozone in the atmosphere in which humans live, work, and play. This is actually a big problem along the Front Range, where we have been out of attainment of the Environmental Protection Agency’s ozone standards:

We expect more of these bad ozone days as climate change ushers in hotter temperatures. If we do not slow climate change or adapt to its effects, this will mean that more people will be exposed to elevated levels of ground level ozone, which makes us sick. Take a look:

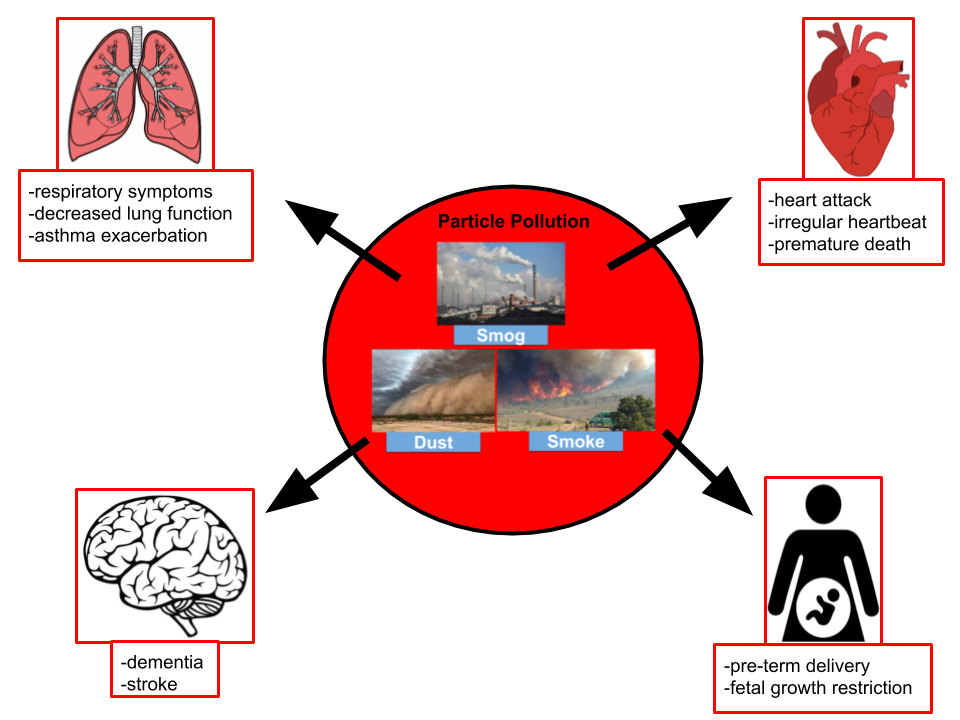

Unfortunately, ozone is not the only climate-related culprit causing poor air quality. Dr. Crooks explains how airborne particle pollution may get worse with climate change, with further bad effects on our health.

But first, what is particle pollution and where does it come from?

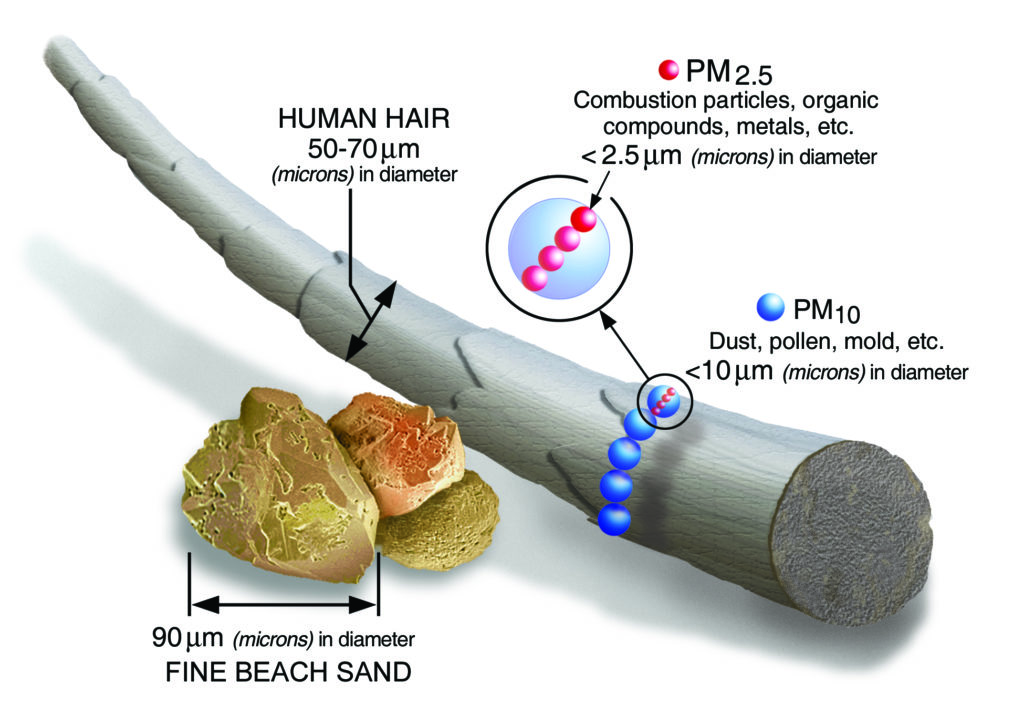

As illustrated in the EPA diagram above, particle pollution is generally categorized into two size categories: PM10 and PM2.5. The “PM” stands for “Particulate Matter”, and the 10 and 2.5 refer to the diameter in microns (AKA micrometers, or 1/1000 of a millimeter) of the particles. The particles less than 2.5 microns can get further down into the lungs and cause more health problems.

Here in Colorado, some of the biggest sources of particle pollution are energy production from combustion (think coal-burning power plant), wildfire, and dust storms in arid, drought-stricken areas. Climate change will likely dry out surface vegetation and worsen drought, which in turn could increase particle pollution from wildfires and dust storms in certain parts of the United States.

How does particle pollution affect health?

The diagram below illustrates a few of the health effects of breathing in particle pollution. Keep in mind that it is not an equal-opportunity harmer: people with pre-existing lung and heart diseases, the young, the old, workers, and those who live near big polluters (industrial sites, highways, etc.) are at greater risk of getting sick from particle pollution.

Shownotes

background readings and resources for the interested listener: